Spiderlife

From J. H. Fabre’s Life of the Spider

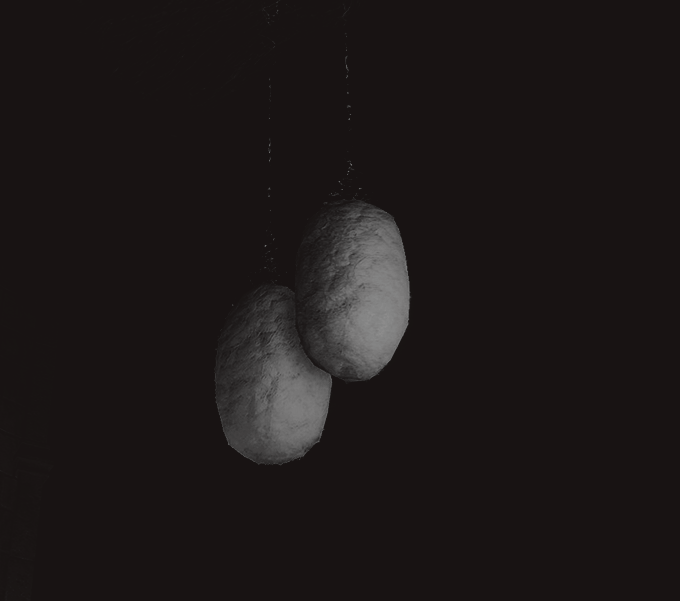

Cocoons hanging from the Brace of Elphael

The little ones are very good: none stirs none tries to get more room for himself at his neighbours' expense. What are they doing there, so quietly? They allow themselves to be carted about, like the young of the opossum. Whether she sit in long meditation at the bottom of her den, or come to the orifice, in mild weather, to bask in the sun, the lycosa never throws off her great-coat of swarming youngsters until the fine season comes.

If, in the middle of winter, in January or February, I happen, out in the fields, to ransack the spider's dwelling, after the rain, snow and frost have battered it and, as a rule, dismantled the bastion at the entrance, I always find her at home, still full of vigour, still carrying her family. This vehicular upbringing lasts five or six months at least, without interruption. The celebrated american carrier, the opossum, who emancipates her offspring after a few weeks' carting, cuts a poor figure beside the lycosa. What do the little ones eat, on the maternal spine? Nothing, so far as I know. I do not see them grow larger. I find them, at the tardy period of their emancipation, just as they were when they left the bag.

During the bad season, the mother herself is extremely abstemious. At long intervals, she accepts, in my jars, a belated locust, whom I have captured, for her benefit, in the sunnier nooks. In order to keep herself in condition, as when she is dug up in the course of my winter excavations, she must therefore sometimes break her fast and come out in search of prey, without, of course, discarding her live mantilla.

The expedition has its dangers. The youngsters may be brushed off by a blade of grass. What becomes of them when they have a fall? Does the mother give them a thought? Does she come to their assistance and help them to regain their place on her back? Not at all. The affection of a spider's heart, divided among some hundreds, can spare but a very feeble portion to each. The lycosa hardly troubles, whether one youngster fall from his place, or six, or all of them. She waits impassively for the victims of the mishap to get out of their own difficulty, which they do, for that matter, and very nimbly.

I sweep the whole family from the back of one of my boarders with a hair-pencil. Not a sign of emotion, not an attempt at search on the part of the denuded one. After trotting about a little on the sand, the dislodged youngsters find, these here, those there, one or other of the mother's legs, spread wide in a circle. By means of these climbing-poles, they swarm to the top and soon the dorsal group resumes its original form. Not one of the lot is missing. The lycosa's sons know their trade as acrobats to perfection: the mother need not trouble her head about their fall.

With a sweep of the pencil, I make the family of one spider fall around another laden with her own family. The dislodged ones nimbly scramble up the legs and climb on the back of their new mother, who kindly allows them to behave as though they belonged to her. There is no room on the abdomen, the regulation resting- place, which is already occupied by the real sons. The invaders thereupon encamp on the front part, beset the thorax and change the carrier into a horrible pin-cushion that no longer bears the least resemblance to a spider form. Meanwhile, the sufferer raises no sort of protest against this access of family. She placidly accepts them all and walks them all about.

The youngsters, on their side, are unable to distinguish between what is permitted and forbidden. Remarkable acrobats that they are, they climb on the first spider that comes along, even when of a different species, provided that she be of a fair size. I place them in the presence of a big epeira marked with a white cross on a pale-orange ground (epeira pallida, oliv. ). The little ones, as soon as they are dislodged from the back of the lycosa their mother, clamber up the stranger without hesitation.

Intolerant of these familiarities, the spider shakes the leg encroached upon and flings the intruders to a distance. The assault is doggedly resumed, to such good purpose that a dozen succeed in hoisting themselves to the top. The epeira, who is not accustomed to the tickling of such a load, turns over on her back and rolls on the ground in the manner of a donkey when his hide is itching. Some are lamed, some are even crushed. This does not deter the others, who repeat the escalade as soon as the epeira is on her legs again. Then come more somersaults, more rollings on the back, until the giddy swarm are all discomfited and leave the spider in peace.